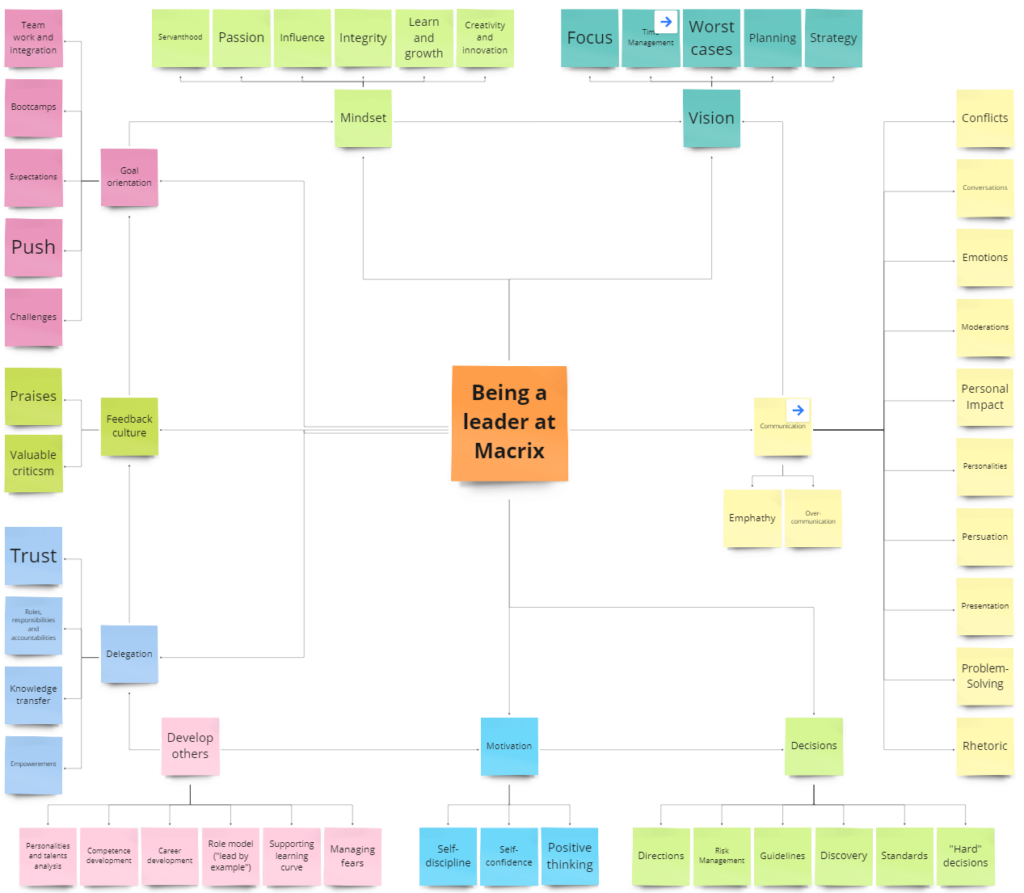

Some years ago, we created a visual map of leadership at Macrix – a colorful chart full of ideas and categories. I recently rediscovered it in our knowledge base. It sparked some thoughts I’d like to share – based on my own leadership journey and experiences over the years.

Over time, I’ve realized that I often start new initiatives by stepping in as a hands-on leader. I observe, learn, adjust, correct, and repeat. That phase helps me understand the reality before I rely on reports or KPIs.

The manager role – delegating, structuring, and stepping back – comes later. Only when there’s trust in people, clarity in processes, and reliable tools in place, do I shift gears.

One mindset I’ve found useful again and again is to assume that, in the beginning, things will go wrong. Not out of pessimism – but to stay alert, prepared, and realistic.

I try to expect little upfront: processes may be unclear, people unsure, toolsnot working yet. That doesn’t mean I don’t trust anyone – it just means I plan for breakdowns. And if things work better than expected, it’s a positive surprise.

Worst-case thinking helps me act early. It prevents disappointment and helps structure initiatives in a way that’s resilient under pressure.

If something is broken, it’s on me. That’s how I’ve come to understand leadership responsibility – and it’s closely aligned with what’s often called Extreme Ownership.

This principle, popularized by Jocko Willink, means taking full responsibility for everything that happens within your environment: the energy in your team, the quality of communication, the clarity of expectations, the results being achieved – or not.

It’s not about doing everything yourself or controlling every detail. It’s about asking:

“What didn’t I see? What did I tolerate? What could I have done differently?”

Leadership responsibility means stepping up even when it’s not technically your fault – because you’re still the one responsible. If people are unclear, it’s up to me to clarify. If something slips through, I need to make sure it doesn’t happen again. If a system fails, I helped design or allow that system.

It also means actively pushing topics forward – following up, checking in, keeping momentum, even when no one explicitly asks for it. I see it as part of my role to notice when things are getting stuck and to help move them. Not for visibility or credit – but because someone has to make sure it happens.

This attitude isn’t about micromanagement. It’s about being attentive to what matters – and caring enough to act when others hesitate or don’t yet see the gap.

Owning outcomes is hard. But it’s also powerful – because it puts you in a position to change things, not just react to them.

Change doesn’t happen just because we announce it. Even a great plan won’t be enough unless people understand it, believe in it, and trust the people driving it. In my experience, successful change requires consistency, over-communication, and real leadership presence.

Resistance to change is natural. It’s not a sign of failure – it’s a signal that people need more clarity, context, or time. I try to treat it as something normal.

Change is never just operational. It’s emotional. That’s why leadership is such a critical part of change management – because if people don’t feel supported from the top, they will disengage.

Clarity and tools may seem different at first – one is abstract, the other concrete. But in leadership, they serve the same purpose: they give people orientation and enable action. Without clarity, people hesitate. Without tools, they get stuck.

At Macrix, we have developed a number of formats and routines that support this. They’re not universal, but they reflect how we try to turn leadership principles into daily practice.

For example, bootcamps and integration processes help us onboard new colleagues with intention – not just technically, but culturally. They create shared understanding and make expectations visible from day one.

Business meetings are another case. Whether it’s a planning sync, decision meeting, or retrospective, we try to ask: Why are we here? What outcome do we need? Are we creating clarity – or just consuming time?

Beyond that, we have the responsibility to use all the instruments available to us:

These are not signs of control – they are signs of care.

They help ensure that what we communicate can actually be done – reliably and well.

One of the most underrated tools in leadership is how we think and speak. I try to follow a simple principle: Think in messages. Say one thing at a time. One point per sentence. One purpose per meeting.

The easiest way to get there is to ask yourself:

“What goal am I trying to achieve in this conversation?”

Thinking about goals helps clarify what’s essential – and what’s just noise. It makes communication more focused, more honest, and more useful to others.

When communication is vague, energy gets lost. When it’s clear, people align.

Leadership communication isn’t about showing what you know – it’s about helping others understand what matters. That’s why I try to shift perspective regularly:

How does this sound to someone new? To someone who is overwhelmed? To someone not in the room?

What seems obvious to me might be confusing to others. Switching perspectives is not a soft skill – it’s a leadership discipline.

Picture: Macrix Gala 2025. Our Gala is a special moment to recognize the true leaders among us, those chosen by our employees themselves. Leadership isn’t defined by a title or position. It’s about attitude, influence, and the way we support each other every day. We believe that anyone can be a leader, and this event is a celebration of that spirit.

Leadership also means enabling others to grow – not just assigning responsibilities, but helping people become ready for them. That includes recognizing strengths and weaknesses, managing fears, and supporting learning curves.

Feedback is a central part of that. Not as a formality, but as an ongoing, honest, and constructive dialogue about progress, behavior, and potential. Good feedback is specific, relevant, and actionable. And it only works when there’s trust on both sides. As leaders, we don’t just give feedback – we build the conditions for it to be heard and used.

Career and competence development goes hand in hand with that. It means identifying potential, offering learning opportunities, opening doors, and guiding people as they grow into new roles. Leadership means being proactive – not waiting for talent to reveal itself, but helping it develop.

Motivation doesn’t come from slogans or emotional speeches. It comes from fairness, recognition, direction – and the sense that what you do actually matters.

I don’t pretend to have all the answers. But I try to lead with presence, reflection, and a strong sense of ownership for the environment I help shape.

Leadership happens in many roles at Macrix: as Managing Directors, Department Heads, Team Leaders, Project Leaders, Lead Developers – and sometimes even without a formal title. Wherever decisions are made, people supported, or problems owned, leadership is present.

The visual attached to this article contains some of the ideas that still resonate with me today. Leadership isn’t a job title. It’s a daily commitment to take responsibility, drive improvement, and be part of the solution.

Attachment: “Being a Leader at Macrix” – a visual from our internal knowledge base that inspired these reflections.